I grew up in an Evangelical Christian home. My family attended Northwest Christian Church in Decatur, Illinois, and some of my earliest memories are of riding in the backseat of my parents’ car on the way to Sunday Morning services, singing “church songs.”

I grew up in an Evangelical Christian home. My family attended Northwest Christian Church in Decatur, Illinois, and some of my earliest memories are of riding in the backseat of my parents’ car on the way to Sunday Morning services, singing “church songs.”

Northwest was part of a decentralized “non-denominational” denomination that arose from something called the Restoration Movement in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Their aim was to restore Christianity to its earliest roots, under the credo “Where the Bible speaks, we speak, and where the Bible is silent, we’re silent.” Although each of the Christian Churches (or Churches of Christ, as they were sometimes called) was independent of any central denominational authority, they were associated with each other through educational institutions and informal networking between the congregations. In our region, Lincoln Christian College (now Lincoln Christian University) was the predominant center of the faith, along with a campground retreat called Little Galilee Christian Assembly, near Clinton, Illinois.

By the time I was in elementary school, I would spend a week each summer at Little Galilee, and once in high school, I would also volunteer at camp, spending as much time there as possible during the summer months. I remember the smell of fresh air, the warm sunshine, the jovial family atmosphere in the dining hall, the bracing refreshment of the pool, the quiet serenity of evening Vespers Service near the lake, pop and candy bars from the canteen, and the sweet possibility of holding a pretty girl’s hand on the long walk to campfire at the end of the day. I was also one of the kids who actually loved Bible study.

Most of all, though, I loved the fellowship, and in particular the fellowship of singing together. There were countless moments of pure joy, caught up in the feeling that we were all one, united in love and bliss.

I was a good little Christian boy, and took seriously what I had been taught – that it was our responsibility to help others find salvation from the fires of hell by accepting Jesus as their Lord, getting baptized, studying their Bible, and doing their best to understand it correctly and live their lives accordingly.

Sometimes we would ride a bus from camp into a nearby town with paperback copies of the New Testament to give away (in a new English translation called Good New for Modern Man). We would go to a shopping center or other public place, and try to strike up conversations with people, offering them the Good News, and inviting them to learn more. We called it “witnessing.”

I stuck to the script, and shared the Bible quotes saying that “all have sinned” and the “wages of sin are death” and that “God so love the world that he sent his only Son” to redeem us from those sins and save from the death we so rightly deserved. But in my heart what I truly wanted to share with people was that feeling of unity and love.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, in case you haven’t heard, a lot of people were turning away from traditional ideas, traditional mores and traditional styles. Clean cut kids trying to recruit people to church were just about as square as you could get. Then somehow, overnight, we weren’t quite so clean cut anymore.

The Jesus Movement, as it came to be called, started on the West Coast as Hippies and other young people began to turn to religion in hopes of finding what they had not found elsewhere. They (mostly) left the drugs behind, but brought with them a healthy portion of counterculture ethics and aesthetics, and suddenly “Jesus People” or “Jesus Freaks” seemed to be blazing their trails everywhere. I was quick to catch the spirit.

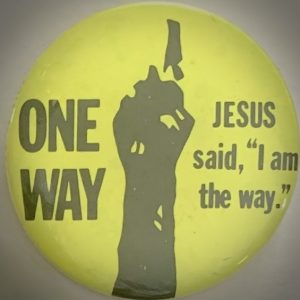

We had our own style, our own way of speaking, our own sense of priorities and (most important to me) our own music. One of the very first songs I learned to play on guitar was Two Hands as performed by Children of the Day. I wore a “One Way” pinback on my guitar strap and long bangs covering my eyes, as summertime sweat soaked a chambray work shirt and moistened the dust on a pair of rope sandals.

“They’ll Know We Are Christians By Our Love” was almost a protest song. Traditional churches had gotten it all wrong, and we were going to change that. As teenagers, we knew better than our parents, and certainly better than the stuffy ministers and elders, with their rules and their neckties and their Brylcreem hair. We were sure that we knew better, and we were also sure that we were better. In our superiority, we were free in our condemnation of their hypocrisy – and their general lack of hipness. Jesus was a long haired, sandal wearing iconoclast too, after all.

The Jesus Movement didn’t last long. Much like our older Hippie siblings most of us got caught up in the pursuits of material reality. We wrapped up our educations, started our jobs, created our families, and gradually took the exit ramps from much of our idealism.

It is fifty years down the road now, and I realized last week that I never entirely found the exit. I don’t thump on the Bible anymore, and I’m unlikely to try to tell other people what they should do or how they should live. I don’t have any interest in railing against hypocrisy, setting towers alight or tilting at windmills. But that yearning to share the feeling of unity and joy and love? It’s for sure still there, whether I like it or not.

It is fifty years down the road now, and I realized last week that I never entirely found the exit. I don’t thump on the Bible anymore, and I’m unlikely to try to tell other people what they should do or how they should live. I don’t have any interest in railing against hypocrisy, setting towers alight or tilting at windmills. But that yearning to share the feeling of unity and joy and love? It’s for sure still there, whether I like it or not.

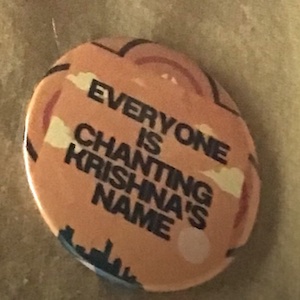

As I pin on a badge that says “Everyone is Chanting Krishna’s Name” and pick up a guitar, I’m that starry eyed kid all over again.

I began chanting the

I began chanting the

We all know the cliché image of a fortune teller, often in Gypsy garb, turning up cards to predict someone’s future. Many a movie plot is hung on such a scene. For people unfamiliar with the Tarot, this is the image that likely first comes to mind when it is mentioned.

We all know the cliché image of a fortune teller, often in Gypsy garb, turning up cards to predict someone’s future. Many a movie plot is hung on such a scene. For people unfamiliar with the Tarot, this is the image that likely first comes to mind when it is mentioned.