In September my wife and I traveled to Western Pennsylvania for an annual retreat with my meditation teacher. Having read about the splendors of Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold nearby, we decided to take a quick detour on our way back home to have a peek.

The building is touted as one of the “40 most beautiful places to visit in the United States” on par with the Biltmore Estate and New York City’s Central Park. Google’s map showed that it was less than thirty miles out of our way, so we took the exit from I-70 near Wheeling, and followed the tortuous winding road to the New Vrindaban complex at Moundsville, West Virginia.

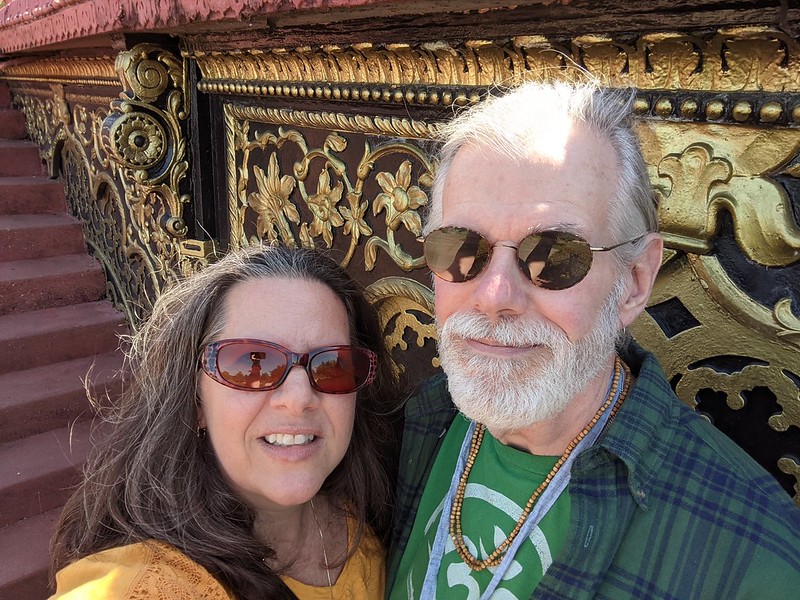

As we walked up the path from the visitor parking lot, we heard music, and Claudia said “Maybe it’s a festival and we’ll be able to have lunch.” I remembered only then that it was Radhashtami, the commemoration of Radha’s appearance on this earth, and a day of celebration for devotees of Krishna such as those at New Vrindaban.

We wandered around a bit, enjoying the views, finally making our way to the entrance of the Palace of Gold where tours begin. A monk – with the classic shaved head, pony tail and orange robes – eventually appeared, asking if we had received prasadam (food that is served at such celebrations). He told us that he was the one who conducted the tours, and that we would have plenty of time to eat before the next one began.

We passed a beautiful lotus pond on our walk down the hill to the picnic area. As we arrived, we were greeted by a devotee named Nityo, who asked “Do we know you?” This seemed like an odd turn of phrase. I responded “I don’t think so,” then related that we were traveling, and had heard of the Palace, and dropped in to tour it.

“So you just happened to be passing through? And you just happened to drop by? And it just happened to be on Radhashtami?” I was beginning to feel a little uncomfortable with the questions, and fumbled for a response. Then he said “And you just happened down the hill when the line for prasadam is empty. Have some food!”

Nityo followed along as we picked up plates and the devotees filled them with amazing vegetarian fare. When Claudia mentioned that she hadn’t smelled such lovely aromas since her trip to India, Nityo asked why she had travelled there. “Do you work for the government?” She explained that her company outsources some work in Chennai.

Our new friend sat with us at table, and the conversation was casual and friendly. At some point, a woman came up and greeted Claudia, called her by another name, and then apologized, saying that she had mistaken her for another devotee who used to live there. There were some other odd exchanges between this woman and Nityo which we took to be none of our business.

As we ate, another devotee brought a fresh garland of jasmine and placed it around Claudia’s shoulders, and handed me a white rose that had been on their altar that morning. We felt like special guests, and marveled at our luck to have arrived on such an auspicious day, and to be treated so well.

We enjoyed the tour of the Palace, and headed on down the road toward home, buoyed by the fragrance of the jasmine, and feeling fortunate at having stumbled into such a delightful experience.

When we arrived home two days later, I did a Google search for our new friend to try to find his email address and send him thanks for the meal and his kindness. What turned up in the search results made the entire episode seem eerie and surreal. It turns out that in the 1980s New Vrindaban had been at the center of a murderous sex scandal.

After the initial shock, as we reflected on our visit, we wondered if our reception there was somehow unusual – if our appearance or manner or the timing of our arrival had created suspicions among the devotees. We speculated that perhaps we fit the profile of snoops of some variety (law enforcement, journalists, disgruntled muck raking former devotees, or what not) and that they welcomed us so warmly in order to keep a close eye on us. Some of the conversation and behavior that we recalled seemed a bit sinister in this context. On the other hand, the gestures of hospitality seemed free and genuine, and while we were actually on the site, we felt no misgivings or signs of anything untoward. In fact, we agreed that we would still be interested in visiting again, even after reading these reports. Despite the jarring revelations, we felt fondness in our hearts for the place and for the people we met there.

We were surprised to learn, last week, of a documentary expose that has just premiered on Peacock, covering the establishment of the settlement, the troubled years during leader Keith Ham’s descent into madness, and the aftermath.

We viewed the series this week. Despite the sensationalistic trailer, and the film’s focus on horrific murders, physical abuse of women devotees, physical and sexual abuse of children in the community’s school system, and other crimes committed under Ham’s leadership, if one cares to be thoughtful the documentary also presents a picture of beauty and devotion which endures among many who still live and worship at New Vrindaban.

If you are interested in watching the film, I would encourage that you do so with an open mind and heart. It is awfully easy to default to judgment and condemnation, especially in these days of cancel culture. I believe that the devotees at New Vrindaban and others associated with the International Society for Krishna Consciousness deserve better.

I would also encourage you to read the ISKCON Communications Ministry’s official response to the film. It comes pretty close to expressing my own sense of things.

Here is an excerpt from another statement released just prior to the debut of the film, which also seems on track. “What we know for certain is that ISKCON is founded on, and aspires for, the highest principles of Vaishnava ethics and values. We also know that we are a society, like every society and religious community, made of human beings with flaws and the human tendency to be covered by material consciousness.”

For me, the most poignant moments of the film were when the sons of one of the murder victims, Charles St. Denis, performed the Vedic rites for their departed father in India, on the Yamuna River at Vrindavan. Also, their testimonies throughout the film, along with those of Detective Thomas Westfall, were some of the most compelling and heart wrenching.

Toward the end of the film, Sergeant Westfall said that he was happy that the community at New Vrindaban was able to recover and heal from their collective trauma. I believe he referred to them as people of hope.

Hope, devotion, kindness and hospitality toward strangers. One could hardly ask for more.