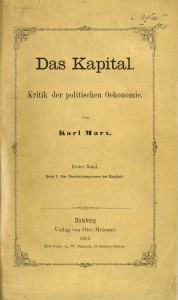

A dear friend and correspondent of mine, Alan Hodge, sent me some food for thought this weekend. It was essentially a criticism of the orthodox Marxist notion of the “dictatorship of the proletariat.”

As a person with a deeply ingrained anti-authoritarian bent, I have studied this question for quite awhile, and continue to struggle with it. Here are some notes outlining my current reasoning of the matter.

Is the establishment of a workers’ state necessary to the project of human liberation?

First, let’s be clear about what we mean by “the state.” It is essentially an institution which uses force or the threat of force, implicit or explicit, to coerce people into obedience. This sounds inherently evil to a lot of us, and we’ve certainly witnessed real life evil perpetrated by the state throughout history and in our own lifetimes. No wonder that it is tempting to simply dismiss any approach to revolution which advocates seizing and wielding state power as part of the plan.

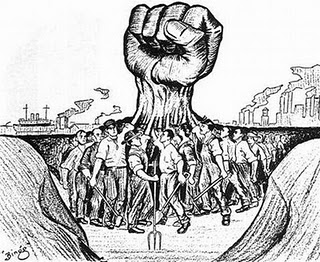

Here’s why we must not only resist, but reject that temptation. The current ruling class already has these means of coercion at their disposal, and time and again have shown no hesitation to employ them. They will not give up their position voluntarily. They will cling to power down to the last tooth and nail.

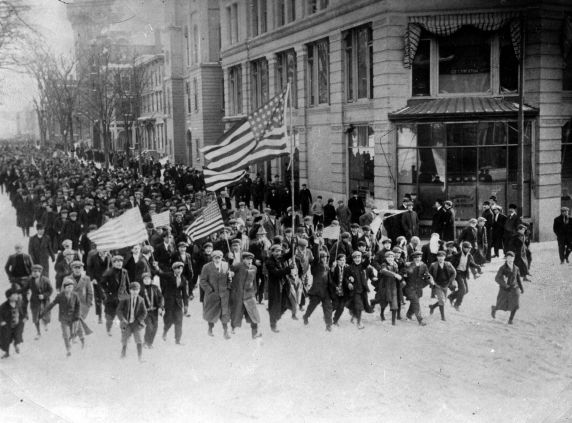

Imagine what would have happened if, after the October revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks had said “Okay, we’re all free now. Everybody cooperate with each other. The state no longer exists.” The old ruling class or another aspiring ruling class would have immediately asserted themselves and seized power. In fact, even with the (albeit deformed) workers’ state in place to act as a bulwark, this is precisely what the reactionary forces, Russian and international, set out to do.

It would be nice to believe, as the anarchists do, that we can establish purely voluntary associations, free of any coercion, to govern society, and that once these organizations are established and federated, an ideal socialist society would take root and flourish without the need for a state. It would be nice to believe in the efficacy of any number of other approaches to worker ascendence, be they cooperatives, or plans to vest workers’ pension funds with control of existing companies’ stocks, or whatever. The fact remains that under any such arrangement there will still be a wealthy and powerful ruling class with which to contend all along the way – a ruling class which enjoys their position of privilege, and will do whatever is in their power to keep it.

Whether we like the idea of a coercive state or we don’t, if we’re going to abandon it as part of the quest for liberty and equality, then we have a responsibility to solve the problem of how to otherwise mitigate the forces of reaction. I’ve not seen a feasible alternative solution proposed to this problem, and, frankly, cannot imagine one.

For those of us who believe that the power of a state will be needed, at least temporarily, in order to achieve human liberation, how can we best ensure against the emergence and entrenchment of new ruling elites?

The notion that Stalin was inevitable has been a part of ruling class ideology and propaganda for three-quarters of a century or more. It is important to reject the inevitability of Stalinism, while at the same time recognizing the danger of Stalinism. The challenge involved in creating deeply democratic structures of power and governance which prevent a new ruling class from putting down roots is daunting. But it begins with how we configure our own organizations of resistance and struggle today. We mustn’t fetishize the models of the Paris Commune or the Russian workers’ councils (“soviets”), but I do think that we can look to them for inspiration. We also need to continue to look at the lessons of history, examine where revolutionaries went wrong in the past, and do our best to create not only structures but cultures of democracy right from the beginning.

Marx believed that it was through the revolutionary struggle itself that the working class would become fit to rule. This may well be the case. It’s not a question to which we yet have a fully satisfactory answer. But unlike the question of the need for a state, there remain, at least, possibilities.