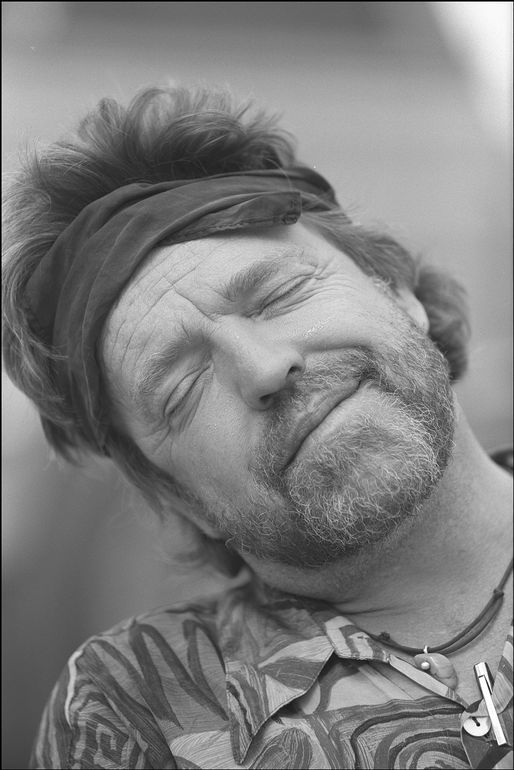

John Perry Barlow

October 3, 1947 – February 7, 2018

Rest in Peace and Power

From NOEBIE.net

Brian K. Noe · ·

Brian K. Noe · ·

These remarks were originally intended to be shared at a film screening to mark the centenary. As that event has been cancelled, I decided to share them here.

On International Women’s Day of 1917 the women textile workers of Petrograd went on strike. They wanted food for their families and an end to the war. Tens of thousands joined them in the streets, and a week later the Russian Tsarist monarchy was no more.

This set into motion eight months of continued struggle, which culminated in the first worker’s state in the history of the world. On October 25th, 1917 (which is November 7th on our current Gregorian Calendar) the Bolsheviks, along with the left wing members of the Menshevik and Socialist Revolutionary parties, having gained a majority in the Congress of Soviets, took power from the final iteration of a provisional government that had stumbled through numerous reconstitutions and attempts to consolidate power since February. The people wanted “peace, land and bread” and the provisional government had failed to deliver.

It was the only revolution in human history that occurred in accordance with a popular democratic vote.

One-hundred years have passed. Why should we still care about the October Revolution?

I’d just like to share a few quotes that I think sum things up pretty well.

The first is from Victor Serge, who was an anarchist who returned to Russia from exile after the revolutions, and joined the Bolsheviks.

“The essential gain of that day, of those years, is the fact that for the first time in history the workers were able to achieve total victory, sustain it, take control of all the levers of command of society, both the economic and the political, get the machine working, and, under the worst conditions, reorganize, despite unbelievable difficulties, all of production on a collective basis. This is what remains and will remain; this is what makes the Russian October shine behind us like a flame that nothing can tarnish.”

There’s also a passage from China Miéville’s excellent history October that’s worth reading. He writes first about the horrors that came under Stalin, and then observes that those who count themselves on the side of the revolution must engage with the failures and crimes that followed in its wake. But he goes on to say:

“It is not for nostalgia’s sake that the strange story of the first socialist revolution in history deserves celebration. The standard of October declares that things changed once, and they might do so again.

“October, for an instant, brings a new kind of power. Fleetingly, there is a shift towards workers’ control of production and the rights of peasants to the land. Equal rights for men and women in work and in marriage, the right to divorce, maternity support. The decriminalisation of homosexuality, 100 years ago. Moves towards national self-determination. Free and universal education, the expansion of literacy. And with literacy comes a cultural explosion, a thirst to learn, the mushrooming of universities and lecture series and adult schools. And though those moments are snuffed out, reversed, become bleak jokes and memories all too soon, it might have been otherwise.

“Twilight, even remembered twilight, is better than no light at all.”

I find it worthwhile to study these events not only to draw inspiration from them, but also in order to better understand what ultimately went wrong, and how we, in our time, might get it right.

And I think it’s particularly important for my countrymen to learn about the great American radicals who were involved in the events of 1917. It’s a history that has been suppressed and hidden and stolen from us, but from them we can learn that fomenting communist revolution is as American as apple pie.

John Reed was an American journalist and political activist who witnessed the revolution first hand on the streets of Petrograd. His masterpiece Ten Days That Shook The World was, at the time of publication, the definitive account of the Russian Revolution. I think that it captures the essence, not only of that moment, but of the revolutionary impulse that is still with us today.

Just at the door of the station stood two soldiers with rifles and bayonets fixed. They were surrounded by about a hundred business men, Government officials and students, who attacked them with passionate argument and epithet. The soldiers were uncomfortable and hurt, like children unjustly scolded.

A tall young man with a supercilious expression, dressed in the uniform of a student, was leading the attack.

“You realise, I presume,” he said insolently, “that by taking up arms against your brothers you are making your-selves the tools of murderers and traitors?”

“Now brother,”answered the soldier earnestly, “you don’t understand. There are two classes, don’t you see, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. We——”

“Oh, I know that silly talk!” broke in the student rudely. “A bunch of ignorant peasants like you hear somebody bawling a few catch-words. You don’t understand what they mean. You just echo them like a lot of parrots.” The crowd laughed. “I’m a Marxian student. And I tell you that this isn’t Socialism you are fighting for. It’s just plain pro-German anarchy!”

“Oh, yes, I know,” answered the soldier, with sweat dripping from his brow. “You are an educated man, that is easy to see, and I am only a simple man. But it seems to me——”

“I suppose,” interrupted the other contemptuously, “that you believe Lenin is a real friend of the proletariat?”

“Yes, I do,” answered the soldier, suffering.

“Well, my friend, do you know that Lenin was sent through Germany in a closed car? Do you know that Lenin took money from the Germans?”

“Well, I don’t know much about that,” answered the soldier stubbornly, “but it seems to me that what he says is what I want to hear, and all the simple men like me. Now there are two classes, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat——”

“You are a fool! Why, my friend, I spent two years in Schlüsselburg for revolutionary activity, when you were still shooting down revolutionists and singing ‘God Save the Tsar!’ My name is Vasili Georgevitch Panyin. Didn’t you ever hear of me?”

“I’m sorry to say I never did,” answered the soldier with humility. “But then, I am not an educated man. You are probably a great hero.”

“I am,” said the student with conviction. “And I am opposed to the Bolsheviki, who are destroying our Russia, our free Revolution. Now how do you account for that?”

The soldier scratched his head. “I can’t account for it at all,” he said, grimacing with the pain of his intellectual processes. “To me it seems perfectly simple—but then, I’m not well educated. It seems like there are only two classes, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie——”

“There you go again with your silly formula!” cried the student.

“——only two classes,” went on the soldier, doggedly.

“And whoever isn’t on one side is on the other…”

Though a century has passed since the events of 1917, the world remains much the same. This is why the experience of those days is still relevant, and worth our consideration. As long as the struggle between a greedy, callous ruling class and a weary, beleaguered working class continues, we shall have recourse to study, to remember and to celebrate Red October.

Brian K. Noe · ·

This was originally written for Learnist. Sadly, that site is no longer online, so I’ll be republishing some of the articles here.

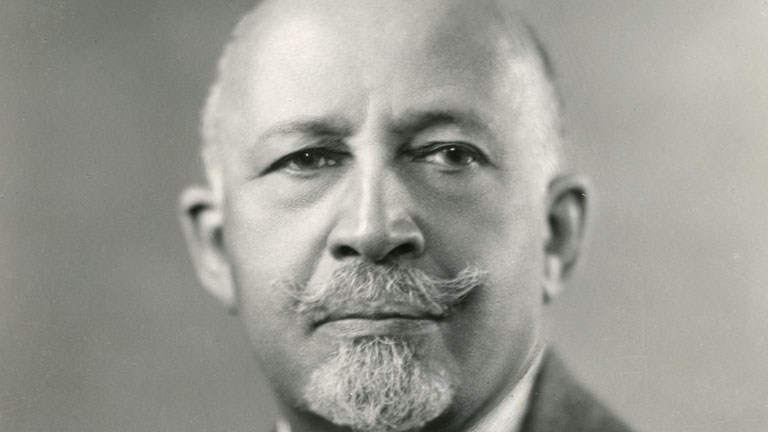

In the first of this series honoring American heroes unknown to many Americans, we remember the great philosopher and freedom fighter W.E.B. Du Bois, founder of the NAACP.

Du Bois’ Early Life in Massachusetts

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in Massachusetts on February 23, 1868, less than three years after the end of the American Civil War. His mother’s grandfather was a slave named Tom Burghardt, who served in the Continental Army during the War of Independence and gained his freedom. Du Bois’ father’s grandfather was a French-American slave owner.

Du Bois’ father left him and his mother when the child was only two years old. They moved into her parent’s home for awhile, and she worked to support herself and her son until she suffered a stroke when Du Bois was in his early teens. She passed from this life when Du Bois was only seventeen years old.

Du Bois attended an integrated public school in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, growing up alongside white classmates in a community that would have been considered “tolerant” for that time. Later in life, Du Bois would write of the racism that was a part of his daily life as a child, despite living in a place that wasn’t formally segregated.

His sharp intellect was apparent to his teachers, and he was encouraged to pursue a higher education. Du Bois would be the first African American to earn a Doctorate from Harvard.

First Experiences in the South

It was during his four years of study from 1885 through 1888 at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, that Du Bois first witnessed and experienced Southern Racism. Formal segregation was the law and lynchings of African Americans were commonplace. In fact, between 1880 and 1930, more than 2000 black men, women, and children were killed by lynch mobs.

A less courageous man might never again have ventured to the South after graduation from Fisk, but Du Bois would return to teach at Atlanta University in 1897.

Address to the Nations of the World

In 1900 Du Bois gave the closing address at the First Pan African Congress held in London.

He began: “In the metropolis of the modern world, in this the closing year of the nineteenth century, there has been assembled a congress of men and women of African blood, to deliberate solemnly upon the present situation and outlook of the darker races of mankind. The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line, the question as to how far differences of race-which show themselves chiefly in the color of the skin and the texture of the hair-will hereafter be made the basis of denying to over half the world the right of sharing to utmost ability the opportunities and privileges of modern civilization.”

He appealed to all people and all nations: “Let the world take no backward step in that slow but sure progress which has successively refused to let the spirit of class, of caste, of privilege, or of birth, debar from life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness a striving human soul.”

Break with Booker T. Washington: The Niagara Movement

After the brutal lynching of Sam Holt in Atlanta in 1899, Du Bois was moved to increasing activism, having grown frustrated with the capitulation of the most well-known and popular African American leader of the time, Booker T. Washington.

Du Bois called for a meeting of black leaders to be held at Niagara Falls, New York. The meeting was eventually held on the Canadian side of the Falls, after being denied accommodations in white hotels on the American side.

They drafted a manifesto that included the following declaration. “We claim for ourselves every single right that belongs to a freeborn American, political, civil and social; and until we get these rights we will never cease to protest and assail the ears of America. The battle we wage is not for ourselves alone but for all true Americans. It is a fight for ideals, lest this, our common fatherland, false to its founding, become in truth the land of the thief and the home of the slave…”

The Souls of Black Folk

In 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois published one of his most influential works, The Souls of Black Folk. It included 14 essays, each chapter beginning with a poetic quote.

A major theme of the book was the dual nature of consciousness for Black Americans.

“After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

“The history of the American Negro,” wrote Du Bois, “is the history of this strife.”

You can read the entire book for free at Project Gutenberg.

The NAACP and The Crisis Magazine

In the wake of the horrific race riots in Springfield, Illinois in 1908, a bi-racial alliance was formed that would become the NAACP.

Founded on the principles expressed by the Niagara Movement, the NAACP’s main goal was to ensure the political, educational, social and economic equality of minority group citizens of the United States and to eliminate race prejudice.

Du Bois founded The Crisis magazine as the premier crusading voice for civil rights. The official magazine of the NAACP, it is now one of the oldest black periodicals in the nation.

The NAACP continues to be a “multiracial army of ordinary women and men from every walk of life, race and class–united to awaken the consciousness of a people and a nation.”

The Harlem Renaissance

In the 1920s and 30s, Harlem became the center of a “spiritual coming of age” ushering in a literary, artistic, and intellectual movement that kindled a new black cultural identity.

In addition to reporting and advocacy, The Crisis became a leading voice of the Harlem Renaissance, as Du Bois published works by Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and other African American literary figures.

Learn more about the Harlem Renaissance in this video from History.com.

Leftist Politics, Peace Activism and Government Repression

Like many great Americans who upheld the ideals of peace, freedom and universal brotherhood, Du Bois became a target for the FBI and McCarthyism.

A longtime activist against imperial warfare, in 1950 Du Bois became chairman of the Peace Information Center, formed to promote the Stockholm Appeal which demanded the outlawing of atomic weapons.

The Justice department required that the Peace Information Center register with the federal government as an “agent of a foreign state.” Du Bois refused and was put to trial. Though the case was dismissed, the government confiscated Du Bois’s passport, holding it for the next eight years.

Du Bois had run for the United States Senate from New York in 1950 on the ticket of the American Labor Party, a group which had split from the Socialist Party of America. His belief that racism around the world was primarily a function of capitalism would eventually lead him to join the Communist Party in the early 1960s, at the age of 93. He reasoned that the Communist ideal was to build a world “whose object is the highest welfare of its people and not merely the profit of a part.”

Du Bois’ Death in Ghana and Enduring Legacy

In October of 1961, Du Bois and his wife traveled to Ghana to work on an encyclopedia of the African diaspora to be called the Encyclopedia Africana. The United States government refused to renew his passport in 1963, so he became a citizen of Ghana, where he died at the age of 95.

By coincidence, the March on Washington was held on August 28, 1963, the day after his death. Although Du Bois did not live to see the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or the Voting Rights Act of 1965, these landmark pieces of legislation codified into the law of the land much of what Du Bois had struggled for his entire life.

His legacy endures today in the work of historians such as Henry Louis Gates and Anthony Appiah, in The Crisis magazine, in the ongoing efforts of the NAACP, and in the struggles of people everywhere who strive for a more just and peaceful world.