Once upon a time, I thought I was a Liberal, and I thought the terms “Left” and “Liberal” meant pretty much the same thing. Then a funny thing happened. I began to read.

Some of the things I began to read were outside of what is often called “the main stream” of American political discourse. I read The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord. It rang true to me, accurately describing our society in a way that I hadn’t seen it described before. It turns out that Debord was a Marxist. Who knew?

I began to have an aching sense that what I believed in my heart to be true was not really reflected in the actions or the statements of the Liberal politicians who generally received my support and approval – people like John Kerry, Dick Durbin, Claire McCaskill or Barack Obama.

At some point, I ran across an interesting tool for defining and assessing a candidate’s or an individual’s political tendencies. It’s called The Political Compass.

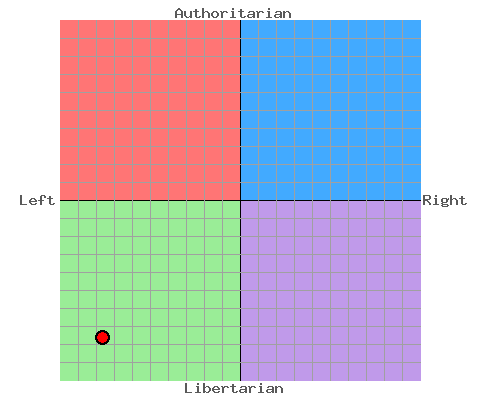

Instead of defining the political spectrum as “Liberal to Conservative” or “Left to Right” the Compass is a Johari Window, with a Libertarian/Authoritarian axis as well as a Left/Right axis. A person can fall into one of four quadrants: Authoritarian Left; Authoritarian Right; Libertarian Left; and, Libertarian Right. Also, degrees and shades within each quadrant are assessed.

I was surprised to learn that I am about as far down in the Libertarian Left as one can be.

That little red dot represents me.

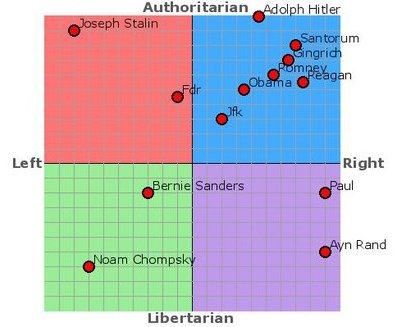

The really astonishing revelation came when I looked at the analysis of historical figures, and current day American politicians. It looked something like this.

Wait a minute. What are my Liberal heroes doing up there in the same quadrant as Reagan? Obama is just barely to the Left economically of Hitler? What the heck is going on here?

As I studied more, I learned that I would be considered a “Left Wing Anarchist/Marxist” based on my answers on the assessment. I wasn’t sure how I felt about that at first. Puzzlement would probably be the best description. I did, however, attempt to learn more about what all of those scary terms mean.

Then another funny thing happened. It was called “Occupy Wall Street.”

Although I didn’t understand precisely what was going on at first, the things I was hearing from the folks in Zuccotti Park rang true to me, in the same way that Debord’s book had, in a way that was a revelation. They were articulating the alienation that I felt, and the injustice that I saw, putting it all into focus for me – giving me a context and vocabulary that I had lacked. Their criticism of the Obama Administration was refreshing. Here was a group of folks being called “the Tea Party of the Left” and yet they seemed to have no interest in catering to the Democrats. By then, neither did I.

Once I gave myself the space and permission to question Liberal orthodoxy, I nurtured my newfound political identity with a wider range of information. I had never read Marx. I had never read Bakunin or Emma Goldman or E.V. Debs or James P. Cannon. I had never listened to the songs of Joe Hill.

I read, and began to search my heart, and realized that I had accepted a lot of ideas that don’t hold up well under closer scrutiny. For instance, almost anything falling into the category of “bipartisan consensus” was tossed by the wayside pretty quickly. The more I questioned, and the more I learned, the more the label “Liberal” became a pejorative term. In fact, in gatherings with other Leftists, I found that calling someone a “Liberal” could be fighting words.

Here’s why this matters and why it is important to correctly name things. When we don’t properly describe the political landscape, it limits the range of discussion and critical thinking that is publicly acceptable. For me, that little bit of space between Obama and Romney is just not enough. When we accept the typical U.S. Liberal/Conservative continuum as the only thing that exists, it precludes an entire world of ideas, analysis, strategies and potential solutions. It also reinforces the “lesser evil” narrative that liberals always trot out in election season. “Yes, we’d like to see more progress too, but this is the real world. Do you want another Scalia on the Supreme Court?”

When we take pains to understand and properly name the entire range of political currents and tendencies, we can also begin to reclaim our history, and to see the connections between the politics of the past and the politics of our own time. We can learn that vigorous, fighting labor unions are the best bulwark against totalitarianism, and realize that opposing Scott Walker’s or Bruce Rauner’s corporatist anti-union agenda places you on the same side of history as those who opposed Adolf Hitler. Such is the great power in naming things accurately and placing them in context.

I would encourage you to take The Political Compass assessment yourself, and learn more about their model and what each quadrant means. It may offer you some new perspectives on our politics and where you fit in. I know where I belong now.

So please, don’t call me a Liberal.